Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It was the first and the largest Kuiper belt object to be discovered. After Pluto was discovered in 1930, it was declared to be the ninth planet from the Sun. Beginning in the 1990s, its status as a planet was questioned following the discovery of several objects of similar size in the Kuiper belt and the scattered disc, including the dwarf planet Eris. This led the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 2006 to formally define the term planet—excluding Pluto and reclassifying it as a dwarf planet.

Pluto is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object directly orbiting the Sun. It is the largest known trans-Neptunian object by volume but is less massive than Eris. Like other Kuiper belt objects, Pluto is primarily made of ice and rock and is relatively small—one-sixth the mass of the Moon and one-third its volume. It has a moderately eccentric and inclined orbit during which it ranges from 30 to 49 astronomical units or AU (4.4–7.4 billion km) from the Sun. This means that Pluto periodically comes closer to the Sun than Neptune, but a stable orbital resonance with Neptune prevents them from colliding. Light from the Sun takes 5.5 hours to reach Pluto at its average distance (39.5 AU).

Pluto has five known moons: Charon (the largest, with a diameter just over half that of Pluto), Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. Pluto and Charon are sometimes considered a binary system because the barycenter of their orbits does not lie within either body.

The New Horizons spacecraft performed a flyby of Pluto on July 14, 2015, becoming the first and, to date, only spacecraft to do so. During its brief flyby, New Horizons made detailed measurements and observations of Pluto and its moons. In September 2016, astronomers announced that the reddish-brown cap of the north pole of Charon is composed of tholins, organic macromolecules that may be ingredients for the emergence of life, and produced from methane, nitrogen and other gases released from the atmosphere of Pluto and transferred 19,000 km (12,000 mi) to the orbiting moon.

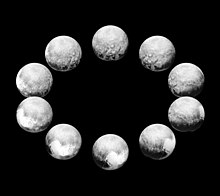

Northern hemisphere of Pluto in true color, taken by NASA’s New Horizons probe in 2015[a]

In the 1840s, Urbain Le Verrier used Newtonian mechanics to predict the position of the then-undiscovered planet Neptune after analyzing perturbations in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent observations of Neptune in the late 19th century led astronomers to speculate that Uranus’s orbit was being disturbed by another planet besides Neptune.

In 1906, Percival Lowell—a wealthy Bostonian who had founded Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894—started an extensive project in search of a possible ninth planet, which he termed “Planet X“. By 1909, Lowell and William H. Pickering had suggested several possible celestial coordinates for such a planet. Lowell and his observatory conducted his search until his death in 1916, but to no avail. Unknown to Lowell, his surveys had captured two faint images of Pluto on March 19 and April 7, 1915, but they were not recognized for what they were. There are fourteen other known precovery observations, with the earliest made by the Yerkes Observatory on August 20, 1909.

Percival’s widow, Constance Lowell, entered into a ten-year legal battle with the Lowell Observatory over her husband’s legacy, and the search for Planet X did not resume until 1929. Vesto Melvin Slipher, the observatory director, gave the job of locating Planet X to 23-year-old Clyde Tombaugh, who had just arrived at the observatory after Slipher had been impressed by a sample of his astronomical drawings.[20]

Tombaugh’s task was to systematically image the night sky in pairs of photographs, then examine each pair and determine whether any objects had shifted position. Using a blink comparator, he rapidly shifted back and forth between views of each of the plates to create the illusion of movement of any objects that had changed position or appearance between photographs. On February 18, 1930, after nearly a year of searching, Tombaugh discovered a possible moving object on photographic plates taken on January 23 and 29. A lesser-quality photograph taken on January 21 helped confirm the movement. After the observatory obtained further confirmatory photographs, news of the discovery was telegraphed to the Harvard College Observatory on March 13, 1930.

Pluto has yet to complete a full orbit of the Sun since its discovery, as one Plutonian year is 247.68 years long.

The discovery made headlines around the globe. Lowell Observatory, which had the right to name the new object, received more than 1,000 suggestions from all over the world, ranging from Atlas to Zymal. Tombaugh urged Slipher to suggest a name for the new object quickly before someone else did. Constance Lowell proposed Zeus, then Percival and finally Constance. These suggestions were disregarded.

The name Pluto, after the Greek/Roman god of the underworld, was proposed by Venetia Burney (1918–2009), an eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology. She suggested it in a conversation with her grandfather Falconer Madan, a former librarian at the University of Oxford‘s Bodleian Library, who passed the name to astronomy professor Herbert Hall Turner, who cabled it to colleagues in the United States.

Pluto compared in size to the Earth and Moon

The discovery made headlines around the globe. Lowell Observatory, which had the right to name the new object, received more than 1,000 suggestions from all over the world, ranging from Atlas to Zymal. Tombaugh urged Slipher to suggest a name for the new object quickly before someone else did. Constance Lowell proposed Zeus, then Percival and finally Constance. These suggestions were disregarded.

The name Pluto, after the Greek/Roman god of the underworld, was proposed by Venetia Burney (1918–2009), an eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology.[26] She suggested it in a conversation with her grandfather Falconer Madan, a former librarian at the University of Oxford‘s Bodleian Library, who passed the name to astronomy professor Herbert Hall Turner, who cabled it to colleagues in the United States.

Mosaic of best-resolution images of Pluto from different angles

Each member of the Lowell Observatory was allowed to vote on a short-list of three potential names: Minerva (which was already the name for an asteroid), Cronus (which had lost reputation through being proposed by the unpopular astronomer Thomas Jefferson Jackson See), and Pluto. Pluto received a unanimous vote. The name was published on May 1, 1930.[26][28] Upon the announcement, Madan gave Venetia £5 (equivalent to 300 GBP, or 450 USD in 2014) as a reward.

The final choice of name was helped in part by the fact that the first two letters of Pluto are the initials of Percival Lowell. Pluto’s astronomical symbol (![]() , Unicode U+2647: ♇) was then created as a monogram constructed from the letters “PL”. The most-common astrological symbol for Pluto in English-language sources is an orb over Pluto’s bident (

, Unicode U+2647: ♇) was then created as a monogram constructed from the letters “PL”. The most-common astrological symbol for Pluto in English-language sources is an orb over Pluto’s bident (![]() , Unicode U+2BD3: ⯓). This symbol was used by NASA after Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet. There are various other symbols in European astrological sources, including ⯔ (

, Unicode U+2BD3: ⯓). This symbol was used by NASA after Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet. There are various other symbols in European astrological sources, including ⯔ (![]() , U+2BD4), ⯕ (

, U+2BD4), ⯕ (![]() /

/![]() , U+2BD5, used in Uranian astrology; also used for Pluto’s moon Charon), ⯖ (

, U+2BD5, used in Uranian astrology; also used for Pluto’s moon Charon), ⯖ (![]() /

/![]() , U+2BD6, found in various orientations, showing Pluto’s orbit cutting across that of Neptune).

, U+2BD6, found in various orientations, showing Pluto’s orbit cutting across that of Neptune).

The name was soon embraced by wider culture. In 1930, Walt Disney was apparently inspired by it when he introduced for Mickey Mouse a canine companion named Pluto, although Disney animator Ben Sharpsteen could not confirm why the name was given. In 1941, Glenn T. Seaborg named the newly created element plutonium after Pluto, in keeping with the tradition of naming elements after newly discovered planets, following uranium, which was named after Uranus, and neptunium, which was named after Neptune.

Most languages use the name “Pluto” in various transliterations. In Japanese, Houei Nojiri suggested the translation Meiōsei (冥王星, “Star of the King (God) of the Underworld”), and this was borrowed into Chinese and Korean. Some languages of India use the name Pluto, but others, such as Hindi, use the name of Yama, the God of Death in Hinduism. Polynesian languages also tend to use the indigenous god of the underworld, as in Māori Whiro. Vietnamese might be expected to follow Chinese, but does not because the Sino-Vietnamese word 冥 minh “dark” is homophonous with 明 minh “bright”. Vietnamese instead uses Yama, which is also a Buddhist deity, in the form of Sao Diêm Vương 星閻王 “Yama’s Star”, derived from Chinese 閻王 Yán Wáng / Yìhm Wòhng “King Yama”.

Once Pluto was found, its faintness and lack of a viewable disc cast doubt on the idea that it was Lowell’s Planet X.[16] Estimates of Pluto’s mass were revised downward throughout the 20th century.

| Year | Mass | Estimate by |

|---|---|---|

| 1915 | 7 Earths | Lowell (prediction for Planet X) |

| 1931 | 1 Earth | Nicholson & Mayall |

| 1948 | 0.1 (1/10) Earth | Kuiper |

| 1976 | 0.01 (1/100) Earth | Cruikshank, Pilcher, & Morrison |

| 1978 | 0.0015 (1/650) Earth | Christy & Harrington |

| 2006 | 0.00218 (1/459) Earth | Buie et al. |

Astronomers initially calculated its mass based on its presumed effect on Neptune and Uranus. In 1931, Pluto was calculated to be roughly the mass of Earth, with further calculations in 1948 bringing the mass down to roughly that of Mars.[40][42] In 1976, Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher and David Morrison of the University of Hawaii calculated Pluto’s albedo for the first time, finding that it matched that for methane ice; this meant Pluto had to be exceptionally luminous for its size and therefore could not be more than 1 percent the mass of Earth.[43] (Pluto’s albedo is 1.4–1.9 times that of Earth.[2])

In 1978, the discovery of Pluto’s moon Charon allowed the measurement of Pluto’s mass for the first time: roughly 0.2% that of Earth, and far too small to account for the discrepancies in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent searches for an alternative Planet X, notably by Robert Sutton Harrington, failed. In 1992, Myles Standish used data from Voyager 2‘s flyby of Neptune in 1989, which had revised the estimates of Neptune’s mass downward by 0.5%—an amount comparable to the mass of Mars—to recalculate its gravitational effect on Uranus. With the new figures added in, the discrepancies, and with them the need for a Planet X, vanished. Today, the majority of scientists agree that Planet X, as Lowell defined it, does not exist. Lowell had made a prediction of Planet X’s orbit and position in 1915 that was fairly close to Pluto’s actual orbit and its position at that time; Ernest W. Brown concluded soon after Pluto’s discovery that this was a coincidence

From 1992 onward, many bodies were discovered orbiting in the same volume as Pluto, showing that Pluto is part of a population of objects called the Kuiper belt. This made its official status as a planet controversial, with many questioning whether Pluto should be considered together with or separately from its surrounding population. Museum and planetarium directors occasionally created controversy by omitting Pluto from planetary models of the Solar System. In February 2000 the Hayden Planetarium in New York City displayed a Solar System model of only eight planets, which made headlines almost a year later.

Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta lost their planet status after the discovery of many other asteroids. Similarly, objects increasingly closer in size to Pluto were discovered in the Kuiper belt region. On July 29, 2005, astronomers at Caltech announced the discovery of a new trans-Neptunian object, Eris, which was substantially more massive than Pluto and the most massive object discovered in the Solar System since Triton in 1846. Its discoverers and the press initially called it the tenth planet, although there was no official consensus at the time on whether to call it a planet.[51] Others in the astronomical community considered the discovery the strongest argument for reclassifying Pluto as a minor planet.

Artistic comparison of Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, Salacia, 2002 MS4, and Earth along with the Moon vte

The debate came to a head in August 2006, with an IAU resolution that created an official definition for the term “planet”. According to this resolution, there are three conditions for an object in the Solar System to be considered a planet:

Pluto fails to meet the third condition.[55] Its mass is substantially less than the combined mass of the other objects in its orbit: 0.07 times, in contrast to Earth, which is 1.7 million times the remaining mass in its orbit (excluding the moon).[56][54] The IAU further decided that bodies that, like Pluto, meet criteria 1 and 2, but do not meet criterion 3 would be called dwarf planets. In September 2006, the IAU included Pluto, and Eris and its moon Dysnomia, in their Minor Planet Catalogue, giving them the official minor-planet designations “(134340) Pluto”, “(136199) Eris”, and “(136199) Eris I Dysnomia”. Had Pluto been included upon its discovery in 1930, it would have likely been designated 1164, following 1163 Saga, which was discovered a month earlier.

There has been some resistance within the astronomical community toward the reclassification.[59][60][61] Alan Stern, principal investigator with NASA‘s New Horizons mission to Pluto, derided the IAU resolution, stating that “the definition stinks, for technical reasons”.[62] Stern contended that, by the terms of the new definition, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune, all of which share their orbits with asteroids, would be excluded.[63] He argued that all big spherical moons, including the Moon, should likewise be considered planets.[64] He also stated that because less than five percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community. Marc W. Buie, then at the Lowell Observatory, petitioned against the definition. Others have supported the IAU. Mike Brown, the astronomer who discovered Eris, said “through this whole crazy, circus-like procedure, somehow the right answer was stumbled on. It’s been a long time coming. Science is self-correcting eventually, even when strong emotions are involved.”[66]

Public reception to the IAU decision was mixed. A resolution introduced in the California State Assembly facetiously called the IAU decision a “scientific heresy”. The New Mexico House of Representatives passed a resolution in honor of Tombaugh, a longtime resident of that state, that declared that Pluto will always be considered a planet while in New Mexican skies and that March 13, 2007, was Pluto Planet Day. The Illinois Senate passed a similar resolution in 2009, on the basis that Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto, was born in Illinois. The resolution asserted that Pluto was “unfairly downgraded to a ‘dwarf’ planet” by the IAU.” Some members of the public have also rejected the change, citing the disagreement within the scientific community on the issue, or for sentimental reasons, maintaining that they have always known Pluto as a planet and will continue to do so regardless of the IAU decision.

In 2006, in its 17th annual words-of-the-year vote, the American Dialect Society voted plutoed as the word of the year. To “pluto” is to “demote or devalue someone or something”.

Researchers on both sides of the debate gathered in August 2008, at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory for a conference that included back-to-back talks on the current IAU definition of a planet. Entitled “The Great Planet Debate”,[74] the conference published a post-conference press release indicating that scientists could not come to a consensus about the definition of planet. In June 2008, the IAU had announced in a press release that the term “plutoid” would henceforth be used to refer to Pluto and other planetary-mass objects that have an orbital semi-major axis greater than that of Neptune, though the term has not seen significant use.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 near the star δ Geminorum, and merely coincidentally crossing the ecliptic at this time of discovery. Pluto moves about 7 degrees east per decade with small apparent retrograde motion as seen from Earth. Pluto was closer to the Sun than Neptune between 1979 and 1999.

Pluto’s orbital period is currently about 248 years. Its orbital characteristics are substantially different from those of the planets, which follow nearly circular orbits around the Sun close to a flat reference plane called the ecliptic. In contrast, Pluto’s orbit is moderately inclined relative to the ecliptic (over 17°) and moderately eccentric (elliptical). This eccentricity means a small region of Pluto’s orbit lies closer to the Sun than Neptune’s. The Pluto–Charon barycenter came to perihelion on September 5, 1989, and was last closer to the Sun than Neptune between February 7, 1979, and February 11, 1999.

Although the 3:2 resonance with Neptune (see below) is maintained, Pluto’s inclination and eccentricity behave in a chaotic manner. Computer simulations can be used to predict its position for several million years (both forward and backward in time), but after intervals much longer than the Lyapunov time of 10–20 million years, calculations become unreliable: Pluto is sensitive to immeasurably small details of the Solar System, hard-to-predict factors that will gradually change Pluto’s position in its orbit.

The semi-major axis of Pluto’s orbit varies between about 39.3 and 39.6 au with a period of about 19,951 years, corresponding to an orbital period varying between 246 and 249 years. The semi-major axis and period are presently getting longer.

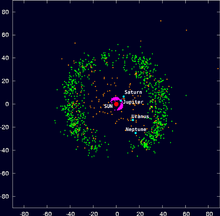

Animation of Pluto‘s orbit from 1900 to 2100

Despite Pluto’s orbit appearing to cross that of Neptune when viewed from directly above, the two objects’ orbits do not intersect. When Pluto is closest to the Sun, and close to Neptune’s orbit as viewed from above, it is also the farthest above Neptune’s path. Pluto’s orbit passes about 8 AU above that of Neptune, preventing a collision.

This alone is not enough to protect Pluto; perturbations from the planets (especially Neptune) could alter Pluto’s orbit (such as its orbital precession) over millions of years so that a collision could be possible. However, Pluto is also protected by its 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune: for every two orbits that Pluto makes around the Sun, Neptune makes three. Each cycle lasts about 495 years. (There are many other objects in this same resonance, called plutinos.) This pattern is such that, in each 495-year cycle, the first time Pluto is near perihelion, Neptune is over 50° behind Pluto. By Pluto’s second perihelion, Neptune will have completed a further one and a half of its own orbits, and so will be nearly 130° ahead of Pluto. Pluto and Neptune’s minimum separation is over 17 AU, which is greater than Pluto’s minimum separation from Uranus (11 AU). The minimum separation between Pluto and Neptune actually occurs near the time of Pluto’s aphelion.

Orbit of Pluto – ecliptic view. This “side view” of Pluto’s orbit (in red) shows its large inclination to the ecliptic.

Numerical studies have shown that over millions of years, the general nature of the alignment between the orbits of Pluto and Neptune does not change.[ There are several other resonances and interactions that enhance Pluto’s stability. These arise principally from two additional mechanisms (besides the 2:3 mean-motion resonance).

First, Pluto’s argument of perihelion, the angle between the point where it crosses the ecliptic and the point where it is closest to the Sun, librates around 90°. This means that when Pluto is closest to the Sun, it is at its farthest above the plane of the Solar System, preventing encounters with Neptune. This is a consequence of the Kozai mechanism, which relates the eccentricity of an orbit to its inclination to a larger perturbing body—in this case, Neptune. Relative to Neptune, the amplitude of libration is 38°, and so the angular separation of Pluto’s perihelion to the orbit of Neptune is always greater than 52° (90°–38°). The closest such angular separation occurs every 10,000 years.

Second, the longitudes of ascending nodes of the two bodies—the points where they cross the ecliptic—are in near-resonance with the above libration. When the two longitudes are the same—that is, when one could draw a straight line through both nodes and the Sun—Pluto’s perihelion lies exactly at 90°, and hence it comes closest to the Sun when it is highest above Neptune’s orbit. This is known as the 1:1 superresonance. All the Jovian planets, particularly Jupiter, play a role in the creation of the superresonance.

In 2012, it was hypothesized that 15810 Arawn could be a quasi-satellite of Pluto, a specific type of co-orbital configuration. According to the hypothesis, the object would be a quasi-satellite of Pluto for about 350,000 years out of every two-million-year period. Measurements made by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2015 made it possible to calculate the orbit of Arawn more accurately. These calculations confirm the overall dynamics described in the hypothesis. However, it is not agreed upon among astronomers whether Arawn should be classified as a quasi-satellite of Pluto based on this motion, since its orbit is primarily controlled by Neptune with only occasional smaller perturbations caused by Pluto.

Orbit of Pluto – polar view. This “view from above” shows how Pluto’s orbit (in red) is less circular than Neptune’s (in blue), and how Pluto is sometimes closer to the Sun than Neptune. The darker sections of both orbits show where they pass below the plane of the ecliptic.

Pluto’s rotation period, its day, is equal to 6.387 Earth days. Like Uranus, Pluto rotates on its “side” in its orbital plane, with an axial tilt of 120°, and so its seasonal variation is extreme; at its solstices, one-fourth of its surface is in continuous daylight, whereas another fourth is in continuous darkness.[95] The reason for this unusual orientation has been debated. Research from the University of Arizona has suggested that it may be due to the way that a body’s spin will always adjust to minimise energy. This could mean a body reorienting itself to put extraneous mass near the equator and regions lacking mass tend towards the poles. This is called polar wander.[96] According to a paper released from the University of Arizona, this could be caused by masses of frozen nitrogen building up in shadowed areas of the dwarf planet. These masses would cause the body to reorient itself, leading to its unusual axial tilt of 120°. The buildup of nitrogen is due to Pluto’s vast distance from the Sun. At the equator, temperatures can drop to −240 °C (−400.0 °F; 33.1 K), causing nitrogen to freeze as water would freeze on Earth. The same effect seen on Pluto would be observed on Earth were the Antarctic ice sheet several times larger.

The plains on Pluto’s surface are composed of more than 98 percent nitrogen ice, with traces of methane and carbon monoxide. Nitrogen and carbon monoxide are most abundant on the anti-Charon face of Pluto (around 180° longitude, where Tombaugh Regio‘s western lobe, Sputnik Planitia, is located), whereas methane is most abundant near 300° east. The mountains are made of water ice. Pluto’s surface is quite varied, with large differences in both brightness and color. Pluto is one of the most contrastive bodies in the Solar System, with as much contrast as Saturn‘s moon Iapetus. The color varies from charcoal black, to dark orange and white. Pluto’s color is more similar to that of Io with slightly more orange and significantly less red than Mars. Notable geographical features include Tombaugh Regio, or the “Heart” (a large bright area on the side opposite Charon), Cthulhu Macula, or the “Whale” (a large dark area on the trailing hemisphere), and the “Brass Knuckles” (a series of equatorial dark areas on the leading hemisphere).

Sputnik Planitia, the western lobe of the “Heart”, is a 1,000 km-wide basin of frozen nitrogen and carbon monoxide ices, divided into polygonal cells, which are interpreted as convection cells that carry floating blocks of water ice crust and sublimation pits towards their margins; there are obvious signs of glacial flows both into and out of the basin. It has no craters that were visible to New Horizons, indicating that its surface is less than 10 million years old. Latest studies have shown that the surface has an age of 180000+90000

−40000 years. The New Horizons science team summarized initial findings as “Pluto displays a surprisingly wide variety of geological landforms, including those resulting from glaciological and surface–atmosphere interactions as well as impact, tectonic, possible cryovolcanic, and mass-wasting processes.

In Western parts of Sputnik Planitia there are fields of transverse dunes formed by the winds blowing from the center of Sputnik Planitia in the direction of surrounding mountains. The dune wavelengths are in the range of 0.4–1 km and they are likely consists of methane particles 200–300 μm in size.

High-resolution MVIC image of Pluto in enhanced color to bring out differences in surface composition

Pluto’s density is 1.860±0.013 g/cm3.[7] Because the decay of radioactive elements would eventually heat the ices enough for the rock to separate from them, scientists expect that Pluto’s internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense core surrounded by a mantle of water ice. The pre–New Horizons estimate for the diameter of the core is 1700 km, 70% of Pluto’s diameter. Pluto has no magnetic field.

It is possible that such heating continues today, creating a subsurface ocean of liquid water 100 to 180 km thick at the core–mantle boundary. In September 2016, scientists at Brown University simulated the impact thought to have formed Sputnik Planitia, and showed that it might have been the result of liquid water upwelling from below after the collision, implying the existence of a subsurface ocean at least 100 km deep. In June 2020, astronomers reported evidence that Pluto may have had a subsurface ocean, and consequently may have been habitable, when it was first formed.

Pluto’s origin and identity had long puzzled astronomers. One early hypothesis was that Pluto was an escaped moon of Neptune knocked out of orbit by Neptune’s largest current moon, Triton. This idea was eventually rejected after dynamical studies showed it to be impossible because Pluto never approaches Neptune in its orbit.

Pluto’s true place in the Solar System began to reveal itself only in 1992, when astronomers began to find small icy objects beyond Neptune that were similar to Pluto not only in orbit but also in size and composition. This trans-Neptunian population is thought to be the source of many short-period comets. Pluto is now known to be the largest member of the Kuiper belt, a stable belt of objects located between 30 and 50 AU from the Sun. As of 2011, surveys of the Kuiper belt to magnitude 21 were nearly complete and any remaining Pluto-sized objects are expected to be beyond 100 AU from the Sun. Like other Kuiper-belt objects (KBOs), Pluto shares features with comets; for example, the solar wind is gradually blowing Pluto’s surface into space.It has been claimed that if Pluto were placed as near to the Sun as Earth, it would develop a tail, as comets do. This claim has been disputed with the argument that Pluto’s escape velocity is too high for this to happen.[158] It has been proposed that Pluto may have formed as a result of the agglomeration of numerous comets and Kuiper-belt objects.[159][160]

Though Pluto is the largest Kuiper belt object discovered,[121] Neptune’s moon Triton, which is slightly larger than Pluto, is similar to it both geologically and atmospherically, and is thought to be a captured Kuiper belt object. Eris (see above) is about the same size as Pluto (though more massive) but is not strictly considered a member of the Kuiper belt population. Rather, it is considered a member of a linked population called the scattered disc.

A large number of Kuiper belt objects, like Pluto, are in a 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune. KBOs with this orbital resonance are called “plutinos“, after Pluto.

Like other members of the Kuiper belt, Pluto is thought to be a residual planetesimal; a component of the original protoplanetary disc around the Sun that failed to fully coalesce into a full-fledged planet. Most astronomers agree that Pluto owes its current position to a sudden migration undergone by Neptune early in the Solar System’s formation. As Neptune migrated outward, it approached the objects in the proto-Kuiper belt, setting one in orbit around itself (Triton), locking others into resonances, and knocking others into chaotic orbits. The objects in the scattered disc, a dynamically unstable region overlapping the Kuiper belt, are thought to have been placed in their current positions by interactions with Neptune’s migrating resonances.[163] A computer model created in 2004 by Alessandro Morbidelli of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice suggested that the migration of Neptune into the Kuiper belt may have been triggered by the formation of a 1:2 resonance between Jupiter and Saturn, which created a gravitational push that propelled both Uranus and Neptune into higher orbits and caused them to switch places, ultimately doubling Neptune’s distance from the Sun. The resultant expulsion of objects from the proto-Kuiper belt could also explain the Late Heavy Bombardment 600 million years after the Solar System’s formation and the origin of the Jupiter trojans. It is possible that Pluto had a near-circular orbit about 33 AU from the Sun before Neptune’s migration perturbed it into a resonant capture. The Nice model requires that there were about a thousand Pluto-sized bodies in the original planetesimal disk, which included Triton and Eris.

Pluto’s visual apparent magnitude averages 15.1, brightening to 13.65 at perihelion. To see it, a telescope is required; around 30 cm (12 in) aperture being desirable.[167] It looks star-like and without a visible disk even in large telescopes, because its angular diameter is only 0.11″.

The earliest maps of Pluto, made in the late 1980s, were brightness maps created from close observations of eclipses by its largest moon, Charon. Observations were made of the change in the total average brightness of the Pluto–Charon system during the eclipses. For example, eclipsing a bright spot on Pluto makes a bigger total brightness change than eclipsing a dark spot. Computer processing of many such observations can be used to create a brightness map. This method can also track changes in brightness over time.

Better maps were produced from images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), which offered higher resolution, and showed considerably more detail, resolving variations several hundred kilometers across, including polar regions and large bright spots. These maps were produced by complex computer processing, which finds the best-fit projected maps for the few pixels of the Hubble images.These remained the most detailed maps of Pluto until the flyby of New Horizons in July 2015, because the two cameras on the HST used for these maps were no longer in service.

The New Horizons spacecraft, which flew by Pluto in July 2015, is the first and so far only attempt to explore Pluto directly. Launched in 2006, it captured its first (distant) images of Pluto in late September 2006 during a test of the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager. The images, taken from a distance of approximately 4.2 billion kilometers, confirmed the spacecraft’s ability to track distant targets, critical for maneuvering toward Pluto and other Kuiper belt objects. In early 2007 the craft made use of a gravity assist from Jupiter.

New Horizons made its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, after a 3,462-day journey across the Solar System. Scientific observations of Pluto began five months before the closest approach and continued for at least a month after the encounter. Observations were conducted using a remote sensing package that included imaging instruments and a radio science investigation tool, as well as spectroscopic and other experiments. The scientific goals of New Horizons were to characterize the global geology and morphology of Pluto and its moon Charon, map their surface composition, and analyze Pluto’s neutral atmosphere and its escape rate. On October 25, 2016, at 05:48 pm ET, the last bit of data (of a total of 50 billion bits of data; or 6.25 gigabytes) was received from New Horizons from its close encounter with Pluto.

Since the New Horizons flyby, scientists have advocated for an orbiter mission that would return to Pluto to fulfill new science objectives. They include mapping the surface at 9.1 m (30 ft) per pixel, observations of Pluto’s smaller satellites, observations of how Pluto changes as it rotates on its axis, investigations of a possible subsurface ocean, and topographic mapping of Pluto’s regions that are covered in long-term darkness due to its axial tilt. The last objective could be accomplished using laser pulses to generate a complete topographic map of Pluto. New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern has advocated for a Cassini-style orbiter that would launch around 2030 (the 100th anniversary of Pluto’s discovery) and use Charon’s gravity to adjust its orbit as needed to fulfill science objectives after arriving at the Pluto system. The orbiter could then use Charon’s gravity to leave the Pluto system and study more KBOs after all Pluto science objectives are completed. A conceptual study funded by the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program describes a fusion-enabled Pluto orbiter and lander based on the Princeton field-reversed configuration reactor.

© 2021 Tüm hakları saklıdır.